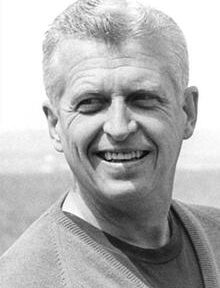

Philip Berrigan

: Photo from Wikipedia / Author of Photo: Unknown AuthorOverview

* Onetime Catholic priest and anti-war activist

* Co-founded the Plowshares movement

* Was frequently imprisoned for his involvement in direct actions

* “I don’t think I’d be anywhere as an activist if I didn’t get authority from the Bible.”

* Died in 2002

Philip Berrigan was born in New Harbors, Minnesota on October 5, 1923. He was the younger brother of Daniel Berrigan. The boys’ father, Thomas Berrigan, was a socialist farmer, railroad engineer, and radical labor organizer. The family moved to Syracuse, New York when Philip was a child, and he was raised there.

Philip Berrigan was drafted into the U.S. military in January 1943. During his basic training in Georgia, he was appalled by the poor living conditions of local black sharecroppers. The racist mistreatment of black soldiers aboard the troop ship to Europe subsequently angered him further. And on the battlefield, Berrigan gradually concluded that armed warfare could not be justified under any circumstances. Indeed, he grew to view himself as no less guilty of murder than the Germans and Japanese, and he condemned nationalistic propaganda where “white Europeans” always triumphed over “anyone else.”After finishing his military service in 1946, Berrigan enrolled at the College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts and went on to earn a degree in English literature (1950). He then committed himself to the priesthood and was ordained in St. Joseph’s Society of the Sacred Heart in 1955. He subsequently earned degrees from Loyola University (bachelor’s in secondary education) and Xavier University (master’s in education).

In the late 1950s Berrigan began teaching at a Josephite high school for black male students in central New Orleans. He became an outspoken advocate for racial justice, and in the Sixties he became active in the burgeoning antiwar movement—particularly after the Cuban Missile crisis of 1962. By Berrigan’s reckoning, social justice and the elimination of racism were inextricably tied to peace activism.

More impetuous and less patient than his brother, Philip Berrigan called for society to be transformed “as soon as possible.”

Berrigan also became active in the nascent civil rights movement and participated in its so-called freedom rides, in which whites and blacks together would intrude on segregated institutions. The radical black activist Stokely Carmichael once described Philip as “the only white man who knows where it’s at.”

As Church authorities in New Orleans grew increasingly uncomfortable with Berrigan’s political activism, they transferred him to the faculty of a Josephite seminary in Newburgh, New York in 1963. From there, Berrigan traveled often to New York City to participate in antiwar and civil-rights events. In 1964 he founded the Emergency Citizens Group Concerned about Vietnam. That same year, Berrigan and his brother Daniel joined several members of the pacifist Catholic Worker Movement (including Thomas Merton) in founding the Catholic Peace Fellowship, which denounced the Vietnam War as immoral.

When addressing a community-affairs council in the mid-1960s, Berrigan asked, “Is it possible for us to be vicious, brutal, immoral and violent at home and be fair, judicious, beneficent and idealistic abroad?” This type of rhetoric displeased Church authorities in Newburgh, who consequently transferred Berrigan to Saint Peter Claver Church, an impoverished black parish in Baltimore, where he served as curate. Berrigan also established the Baltimore Interfaith Peace Mission, which led antiwar demonstrations in both Baltimore and Washington, D.C.

In 1965 Berrigan charged that America’s military involvement in Southeast Asia was rooted in racism. Soon thereafter, he and his brother Daniel signed a Declaration of Conscience publicly urging resistance to the draft. Berrigan also formed clubs that pressured landlords to repair buildings in black ghettoes.

In 1965 as well, Berrigan was a founder of Clergy and Laity Concerned About Vietnam, along with other notables like his brother (Daniel) and William Sloane Coffin.

In 1966 Berrigan was a sponsor of the Ann Arbor, Michigan-based Radical Education Project, which described itself as “an independent education, research and publication program, initiated by Students for a Democratic Society, devoted to the cause of democratic radicalism and aspiring to the creation of a new left in America.”

In December 1966 Berrigan and other clergymen picketed the D.C. homes of U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.

By 1967 Berrigan had abandoned the concept of passive resistance and declared himself a revolutionary for the cause of peace and social justice. On October 27 of that year, he and three others (including his brother Daniel) marched into the Selective Service Office at the Customs House in Baltimore and dumped vials of animal blood (mixed with a small amount of their own blood) on hundreds of draft records (including those of Philip Berrigan himself), to symbolically protest the spilling of human blood in Vietnam. Arrested and charged with defacing government property and disrupting the Selective Service system, Berrigan was sentenced to six years in prison.

Even before that sentencing, Berrigan recruited eight accomplices (including his brother Daniel) to raid the local draft board office in Catonsville, Maryland on May 17, 1968. There, the “Catonsville Nine” took possession of 378 draft-board files, brought them outside to the parking lot, and set them ablaze with homemade napalm (a mixture of gasoline and soap chips). They then recited The Lord’s Prayer aloud and waited for the police to come and arrest them. (The Berrigan brothers were both dressed in their priestly vestments.) They also issued a statement to the press:

“We are Catholic Christians who take our faith seriously. We use napalm because it has burned people to death in Vietnam, Guatemala and Peru and because it may be used in American ghettoes. We destroy these draft records not only because they exploit our young men but also because they represent misplaced power concentrated in the ruling class of America. We believe some property has no right to exist. We confront the Catholic Church, other Christian bodies, and the synagogues of America with their silence and cowardice in the face of our country’s crimes.”

In the 1968 trial of the Catonsville Nine, all the defendants were found guilty. Berrigan, for his part, was sentenced to three-and-a-half years in prison—to be served concurrently with the six-year sentence from the Baltimore conviction—but was released on bail, pending his appeal. But when that appeal was ultimately denied in early 1970, Berrigan and his brother Daniel—both of whom were scheduled to report for prison on April 9 of that year—decided to go underground in an effort to elude the law while continuing to spread their antiwar message. Both men’s names were promptly added to the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list. Philip Berrigan was located and arrested by FBI agents in St. Gregory’s Church in Manhattan on April 21, 1970, and was immediately incarcerated at the federal penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. Daniel, for his part, eluded capture until August 11.

The drama of the Catonsville incident and its aftermath elevated the Berrigan brothers to the status of icons of the Left. Berrigan spent much of his time in prison praying and filling journals with polemical writings about the Catholic Church, America, politics, and many other subjects.

Prior to his incarceration, Berrigan had fallen in love with a nun, Elizabeth McAlister of the Religious Order of the Sacred Heart, and the two had secretly declared themselves husband-and-wife in a 1969 ceremony without witnesses. Now, they used the services of Boyd Douglas, a young inmate whom they both trusted and who was allowed to leave the prison compound in order to attend college classes, to smuggle their love letters past the prison censors. Some of those letters discussed plans to kidnap Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and place him on mock trial for war crimes; others mentioned plans to conduct acts of anti-government violence, such as blowing up heating tunnels under federal buildings in Washington. Unbeknownst to Berrigan and McAlister, Douglas was an FBI informant who forwarded their letters to his connections in the Bureau. Berrigan and McAlister were eventually indicted for conspiracy, but in their 1972 trial they were convicted only of letter smuggling. Berrigan was paroled in December 1972, and an appeals court later dismissed the letter-smuggling conviction.

After his release from prison, Berrigan became an activist against America’s development of nuclear arms, which he condemned as “the scourge of the earth.” “To mine for them, manufacture them, deploy them, use them, is a curse against God, the human family, and the earth itself,” said Berrigan.

In 1973 Berrigan and McAlister legalized their marriage, and both were promptly excommunicated from the Catholic Church. They went on to create Jonah House, a Baltimore-based commune of anti-war activists who used biblical scripture as the basis upon which they condemned all armed conflict—regardless of the circumstances. According to Jonah House, “The U.S. is the world’s #1 terrorist” and should “disarm now.”

In the mid-1970s, Berrigan served on the advisory board of the New York-based Political Rights Defense Fund, which was created to fight FBI surveillance of the Socialist Workers Party and its youth arm, the Young Socialist Alliance.

In October 1975 Berrigan and 21 followers were arrested at an airfield in East Hartford, Connecticut, for defacing military aircraft with a red liquid symbolizing blood. When authorities took into consideration that the planes had not been seriously damaged in any way, they dropped the charges.

After the fall of South Vietnam in 1975 triggered a mass exodus of refugees from that country, singer Joan Baez offered Berrigan an opportunity to join several dozen other prominent individuals (including his brother Daniel) in signing a May 30, 1979 open letter (published in The New York Times) exhorting the North Vietnamese conquerors to treat their prisoners humanely. But Berrigan refused.

In 1980 Berrigan and seven collaborators (including his brother Daniel) created a nuclear arms abolitionist movement known as Plowshares, whose initial public act was to raid a General Electric plant in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania which manufactured nuclear missiles. There, the “Plowshares Eight” pounded missile casings with hammers in a symbolic attempt to “beat swords into plowshares” (a phrase from Biblical passages in Isaiah [2:4] and Micah [4:3]). They also poured animal blood onto documents at the site. Berrigan was again sentenced to a prison term, but was later paroled for time already served.

In the ensuing years, Berrigan participated in many additional Plowshares demonstrations and was arrested numerous times. His final Plowshares action took place in 1999, when he and some fellow activists tried to sabotage a group of A-10 Warthog warplanes stationed at the Middle River Air National Guard base. Berrigan was sentenced to 30 months in prison for his involvement, and was released in 2001. Between 1980-2000, he served various prison sentences totaling about eleven years in all.

In 1994 Berrigan was an initiator—along with Philip Agee, Noam Chomsky, John Conyers and Charles Rangel—of the Peace for Cuba International Appeal (PCIA), which called for increased trade with, and travel between, the United States and Fidel Castro‘s Cuba.

Post-9/11, Berrigan turned his focus toward condemning the Bush administration for such transgressions as “the stolen [2000] election in Florida”; “adhering to a [policy] … which went beyond the war in Afghanistan—which, of course, was an enormous swindle in itself”; and the invasion of Iraq in pursuit of “control of the Middle East and its oil.” In a letter to President Bush, Berrigan and his wife together stated: “We know that your war against terrorism is a colossal sham. How can the supreme terrorist nation wage war against terrorism? Does a new war annually and four nuclear wars (Hiroshima and Nagasaki; Iraq; Yugoslavia; and Afghanistan) not qualify as terrorism?”

Berrigan endorsed an October 6, 2002 demonstration against “the U.S. government’s war on the world,” “detentions and roundups of immigrants,” and “attacks on civil liberties.” The protest was organized by Not In Our Name, a project initiated by the longtime Maoist activist and Revolutionary Communist Party member C. Clark Kissinger. Two of the featured guest speakers were the terrorist financier Sami Al-Arian and radical attorney Lynne Stewart.

Berrigan died of cancer on December 6, 2002, in Baltimore.

Additional Resources:

Further Reading: “Philip Berrigan, Former Priest and Peace Advocate in the Vietnam War Era, Dies at 79” (NY Times, 12-8-2002); “Daniel Berrigan” (YourDictionary.com, American National Biography); “Daniel Berrigan [Obituary]” (The Guardian, 12-11-2002); American Dissidents (edited by Kathlyn Gay, 2012, pp. 63-66); American Social Leaders and Activists (by Neil Hamilton, pp. 45-47); “Philip F. Berrigan, 79 [Obituary]” (Los Angeles Times, 12-8-2002); “Peacemaking: Images from the Jonah House Archive, 1967-1973” (JonahHouse.org).